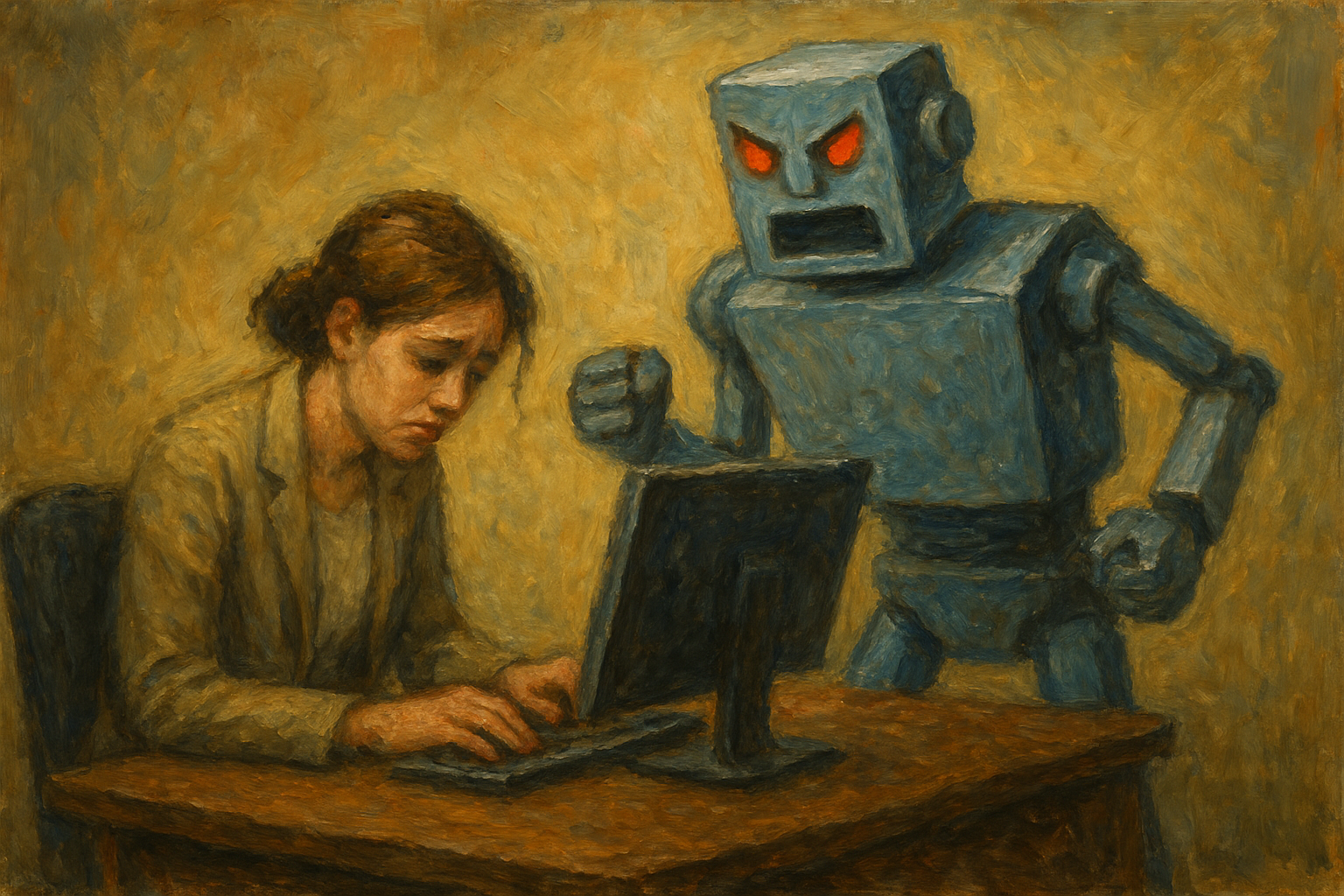

Slowly Surrendering to our AI Masters

Lately, I’ve been feeling like AI is an existential threat to my continued employment, like the result of whether I’ll be able to keep feeding my family or get pushed out of the field hinges on how effectively I can use these new tools. Fortunately, I work for a company that values experimentation and learning with AI, so I have both the freedom and the support to explore.

Getting Out of the IDE

When I first started playing around with language models, I thought the whole point was to write code directly inside an editor the way I’ve always done. That approach was frustrating and re-enforced my belief that AI models are an interesting toy but not capable of producing serious, reliable code.

That assumption broke when I read a Hacker News thread about a developer who goes to his desktop app instead of typing in his IDE. He’d ask the AI to sketch out a function, then go back and forth and copy the final snippet into his IDE to do the final tweaks manually.

It struck me that the AI wasn’t replacing the IDE; it was becoming another helper tool. I tried the same workflow: I opened Claude desktop, gave it read access to my repository, and asked it to propose solutions to the problem I was solving. The rest—adding tests, refactoring, integrating with the other domains in the system—remained firmly in my hands.

That experience taught me two things: first, AI can generate useful code on its own, but you still need to bring it into your existing toolchain; second, the “real” power comes from using the model as a collaborator that suggests ideas, not as a replacement for your IDE. It feels less like a threat and more like an extra pair of hands.

At some point I said that AI isn’t coming for your jobs, people who use AI effectively are coming… and that feels more true than ever before.

Why Longer Prompts Matter

In my early days of experimenting with LLMs, I would just type a short command to create a small feature, then issue more short commands to tweak the feature and debug it until I was satisfied. The output was quick, but it was also generic—no error handling, no documentation, no overall purpose. I kept hammering away at the prompt until I got something that worked in my test case. It took a lot of time, used a lot of tokens, and left me frustrated with the LLM as a tool.

Then I heard about about spec‑driven development. Instead of telling the model what to do after the fact, I asked it to write a specification first, to tell me what it planned to do and why it thought that way. The model produced a concise spec, then we refined it together - adding edge cases, asking what information the model was missing to build without hallucinations, making sure the rules were internally consistent.

Once I had that detailed spec, I fed it back into the prompt as a single long request. The result was a fully‑documented application with a graphical UI, terrain generation and complex build logic, with no bugs. Not quite a playable game, but easily weeks of work compressed down into a single evening.

That shift from “do this, now do this” to “what’s the full picture?” made the AI far more helpful. It feels like I’m co‑authoring a design document before I write code, which in turn reduces surprises when I get the final result.

Unexpressed Values Show Up as Bugs

My main beef with code that Claude and Gemini and ChatGPT produced was the quality seemed akin to a junior developer just out of college. Yes it might be functionally correct, but it missed all the principals that make good software and left me spending more time debugging than if I had just written the thing myself in the first place.

I mentioned this to a CTO friend and he pointed out that most developers have personal coding philosophies - some love concise functional style, others prefer explicit OOP patterns. The LLM model is trained on massive datasets of varying quality from the Internet. If your specific beliefs aren’t communicated to the AI, it defaults to its internal biases which can clash with yours.

So every time I got an output that bothered me from the AI, I woudl evaluate what it was that bothered me about the code, and express the correct methodology in my project file. When I re-ran the prompt, the bot started producing code that was closer and closer to the level of quality I would expect from my own.

Epiphany

They may not be major insights but those insights have transformed my workflow. I’m using these tools in as many places as I can find use for them - checking my work, tweaking my communications, organizing my chaotic thoughts into managable TODO lists. I feel so much more focused in my work, almost like I have an assistant running interference for me so I can focus on the most critical tasks.

Each new prompt feels like setting up a puzzle. I outline the goal, play with different phrasings and see how closely the AI’s output lined up with my mental image. It’s a loop of question, answer, refine much like a game where you learn the rules by trial and error.

The fun part? Every iteration teaches me something new about how to phrase requests or what specifications are most useful. I’m no longer just waiting for code or feedback from other developers; I’m actively shaping the conversation with the model. It’s less “I need help” and more “let’s see how close we can get.”

I’ve held a lot of jobs where clearly communicating my intent is important to keep the team aligned. Synthesizing my thoughts in a structured accessible way has always been a battle, and I finally have a tool that is challenging me to massively improve at that.